Disclaimer: I’m not a battery engineer. I’m documenting what I’m building and what I learned—verify safety-critical decisions with qualified experts.”

If you’re converting a car to electric, you’ll quickly discover something: the motor is the easy part. The real work is the traction battery.

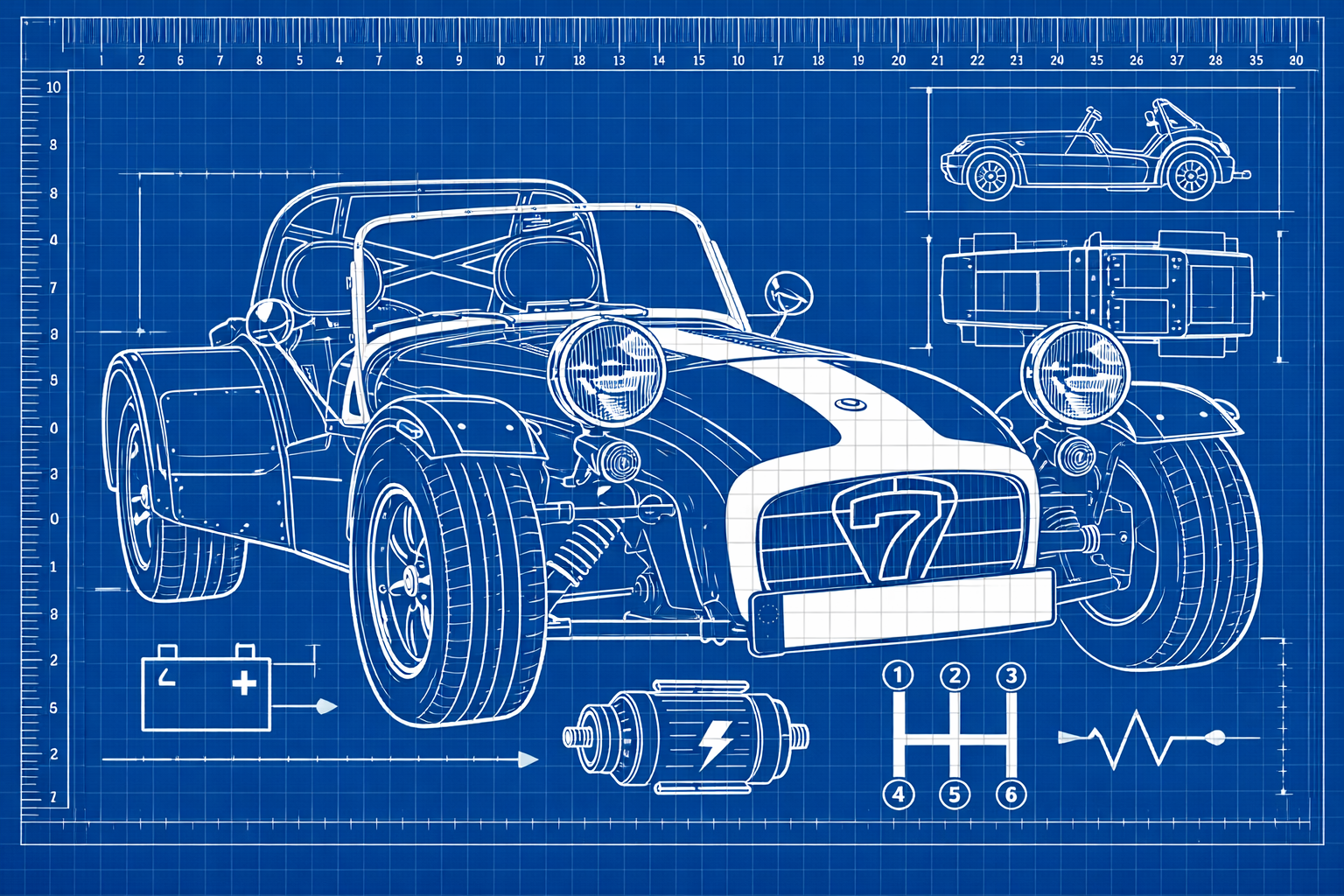

This series walks you through designing an EV incl. battery box from scratch, based on my own manual transmission conversion project.

Why the battery is the real challenge

Coming from the combustion world, the natural starting point is the motor. From there, you pick an inverter to match. Both are largely off-the-shelf components you can specify in a day or two.

Then you hit the battery pack.

This is where the real work begins. Building an EV isn’t hard because of the happy path—starting the motor, driving around, having fun. It’s hard because you need to make the battery safe to work with during assembly, safe during normal operation, and critically, safe in an accident. The battery is simultaneously your energy storage, your biggest safety liability, and the most complex subsystem in the car.

Unlike a motor or inverter you can buy as a unit, a battery pack is something you often have to design and build yourself, especially in a conversion project.

System overview

For my Caterham conversion project, I opted for a split battery system. I chose this configuration to maximize capacity and maintain a weight distribution roughly the same as the original setup.

Here is an overview of the system: (latest version always available in my github)

Next I’ll cover a few components that aren’t super common outside EVs.

Deep dive on selected components

This section talks briefly about 3 system components that are very specific to electric vehicles.

IMD – Isolation Monitoring Device

In a high-voltage EV system, you typically want the HV battery to be galvanically isolated from the vehicle chassis (reference ground). If a fault connects HV to chassis, touching the wrong metal part at the wrong time can become dangerous.

An IMD continuously monitors insulation resistance between the HV system and chassis—practically speaking, it checks whether either pole is leaking to ground (it’s not just the negative pole). If insulation resistance drops below a threshold, the system triggers a shutdown path (often via the safety loop), which results in opening the main contactors (AIRs) and isolating the pack from the rest of the car.

Typical causes include damaged cables, pinched insulation, moisture ingress, or crash damage leading to unintended chassis contact.

Precharge circuit

Every inverter (and many HV devices) has input capacitance on the DC link. If you connect a battery directly to an “empty” DC link, you get an inrush current spike that can weld contactors, stress connectors, and generally make your day worse.

A precharge circuit solves this by charging the DC link gently through a resistor before the full connection is made.

A common startup sequence looks like this:

- Precharge contactor closes (current flows through a resistor into the HV bus / inverter capacitors).

- The system watches bus voltage rise until it reaches a threshold (often ~90–95% of pack voltage).

- Main contactors (AIRs) close to connect the pack directly.

- Precharge contactor opens (the resistor is bypassed/removed from the circuit).

In my project I’m starting with a relatively high precharge resistance (e.g. 820 Ω) because I want a slower, more “ceremonial” ramp. That’s a preference not a universal recommendation. Precharge values are a trade-off between time, resistor power dissipation, and inrush limitation.

Discharge circuit

When the contactors open (shutdown, fault, service), you don’t want high voltage on the “outside” HV bus. Between inverter capacitors and DC/DC converters there can be meaningful stored energy even after disconnect.

That’s why you need a discharge path for the HV bus. You can do this with:

- an active discharge (controlled, switched, faster), or

- a passive bleeder (simple, always present, slower)

For simplicity, I went with a constant bleeder. The range impact is small, and the system stays simple. In my architecture, that means a resistor connected across the HV output on the load side of the contactors, so it can bleed down the external HV system when the pack is disconnected.

Core components of a battery system

Let’s break down the components you need in a battery system. I’m assuming you’re working with modules (like repurposed EV modules) rather than raw cells, which is the practical choice for most conversions.

Connectors

- HV Connector: connects pack HV output to the rest of the car (inverter, secondary pack, etc.)

- e.g. HVSL1200022A1H10

- LV Connector: carries low-voltage signals (CAN, interlocks, enable lines, sense, etc.)

- e.g. DTM06-12SA

Safety & isolation

- AIR (Accumulator Isolation Relays) — High-voltage contactors that disconnect the battery in emergencies or during shutdown

- e.g. EV200HAANA

- MSD (Manual Service Disconnect) — Physical plug or lever to completely isolate the pack for safe servicing

- e.g. MINIMSDF000F

- Fuse — Overcurrent protection to prevent thermal runaway from short circuits

- IMD (Isolation Monitoring Device) — Continuously monitors insulation resistance to detect ground faults before they become dangerous

- Potentially integrated in the BMS which is the case for the Orion 2, otherwise Bender is a widely used brand.

Power management

- Battery modules — The energy storage cells themselves, typically lithium-ion in some form

- e.g. Used Volkswagen Modules (ID3) – https://evshop.eu/en/batteries/345-vw-id3-battery-module-30v-8s-685kwh.html

- BMS (Battery Management System) — Monitors individual cell voltages and temperatures, balances cells, and acts as the pack’s safety watchdog

- e.g the Orion 2 from Orion BMS

- Precharge circuit — Gradually charges the inverter’s capacitors before closing the main contactors (prevents damaging inrush current)

- Discharge circuit — Safely bleeds down residual voltage when the system shuts down

Sensing & control

- Current sensor — Measures pack current for state-of-charge estimation and power limiting

- Look for products that are packaged with the BMS – the EU Distributor for the Orion (evshop.eu) offers a compatible one

- Voltage sensor — Monitors total pack voltage and monitors state and functionality of discharge circuit

- I use the IVT-S sensor from Glashütte – mainly because it has a compatible digital interface with my VCU

- VCU (Vehicle Control Unit) — The brain that orchestrates startup sequences, monitors safety conditions, and coordinates all subsystems

- e.g. VCU300 from AEM electronics

Charging & drive

- DC/DC converter (HV → 12V) — Keeps the 12V system alive (powers the BMS, VCU, and other control electronics) through the HV battery

- High-voltage charger — Charges the main battery pack (AC charging in my case)

- Inverter — Converts DC battery power to AC for the motor

- Electric motor — Converts electrical energy into mechanical motion

I’ve kept descriptions brief here—the goal of this post is to give you an overview about the core components. Now that the system design is done and the mechanical design is underway – the next post will cover the first integration topics!